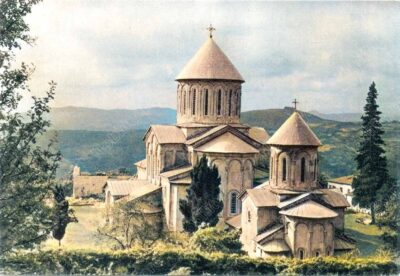

Gelati Monastery – Leave Kutaisi from the northwest by David Agmashenebeli (the Builder) Street, which becomes Gelati Street, and proceed along this road for seven km (four miles). A sign beyond the village of Gelati marks the right-hand turnoff.

Beautifully situated on a forest-covered hill high above the Tskhaltsitela River, the Gelati Monastery complex consists of the main church (Cathedral of the Virgin), the Church of St. George (cast of the main church), the Church of St. Nicholas (west of the main church), the Belltower, the Academy Building (west of the Church of St. Nicholas), the South Entrance and the Chapel containing the tomb of King David Agmashenebeli.

The monastery was founded in 1106 by King David the Builder (1089-1125) at a time when Kutaisi was the capital of a united Georgia and Tbilisi was still an Arab emirate. King David built the monastery out of gratitude to God for his early victories against the Seljuk Turks. He also wanted to found a new Athos or new Jerusalem to serve as a center of Christendom as he consolidated power and expanded his empire.

Gelati therefore, was intended as both a royal monastery- and an academy. David brought famous theologians trained in philosophy such as Arsen Ikaltoeli and loane Petritsi to teach at the academy. Both had been professors at the Mangana Academy in Constantinople but were ousted on account of their Neoplatonist philosophies. They did, however, organize the Academy at Gelati along the lines of Mangana. The curriculum consisted of geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, music, rhetoric, grammar, philosophy. Greek, and Latin.

Petritsi, the first director of Gelati, returned to his homeland after also working for a long period in the Georgian Monastery of Bachkovo at Petritsoni in Bulgaria. He translated numerous philosophical works from Greek into Georgian and is widely credited with the development of philosophy in his country. So great was the influence of the Academy at Gelati that it eclipsed the Georgian centers at Athos, the Holy Cross in Jerusalem, and Petritsoni in Bulgaria.

The plastic arts also were by no means neglected at Gelati. The school of painters at the monastery was the most important one of the time in the entire country. Manuscript illumination was practiced, as were gold and silver forging, which reached a high degree of artistry. The artists of the monastery produced the sumptuous gold, silver, and enamel frame for the Khakhuli Triptych, now in the Treasury of the Museum of Georgian Art. From King Demtre I, David’s son, to all subsequent Georgian kings, each considered it his duty to lavish riches upon the monastery in the form of land, manuscripts, icons, and money.

This tribute continued until the monastery’s gradual decline in the 14th century. The Turks looted and burned Gelati in 1510. In 1759 the monastery was sacked and burned again, this time by the Lezgians (a northern Caucasian tribe). Despite the efforts at preservation and rebuilding by the Imeretian kings throughout these years, many important works of art were lost and the buildings severely damaged.

Gelati never regained its former significance. In 1922, after Georgia had been annexed to Russia by the Bolsheviks (in 1921), the monks living in Gelati were dispersed. Only in 1988 was the monastery once more revived with the reconsecration of the Cathedral of the Virgin and the Church of St. George.

Though the two smaller churches of St. George and St Nicholas were built in the 13th century, two centuries after the main Cathedral of the Virgin, the entire monastery ensemble shows a unity in its configuration and a harmony in the building materials used.

The Cathedral of the Virgin

David the Builder did not live to see the completion of the cathedral (1125), begun as the centerpiece of the monastery complex in 1106. Finished and consecrated to the Virgin Mary by Davids son Demetre I in 1125, the central-domed cruciform church 15 built of pale yellow and gray limestone upon which a minimum of decorative embellishment has been carved.

Blind arcading and molding on door and window frames are present, but restrained, on ever)’ side of the facade. The narthex in the west and the chapel in the south were added in the 12th and 13th centuries; the addition in the north dates from the 13th and 14th centuries. These structures replaced an ambulatory that had originally been designed to wrap around three sides but was never executed. The additions provide another level in the visual ascent to the drum and cupola, which imparts an increased dynamism to the structure.

This mobility is enhanced by the steep pitch of the roofs and the decorative gables. The projecting polygonal apses in the cast are reminiscent of certain churches on the Black Sea Coast, such as the one at Bichvinta, which is atypical of the flat eastern facade marking Georgian churches. Given the restrained aspects of exterior decoration here, it seems not unreasonable to surmise that special emphasis on interior decoration was always intended.

As is common in 11th-century churches in Georgia, the cupola sits on the ends of the walls of the apse in the east and on freestanding massive piers, quadrangles covered in frescoes, in the west. The windows in the drum and large windows in the choir gallery as well as in the west, north, and south walls illuminate the space, creating admirable conditions in which to view what are among the best-preserved frescoes in all Georgia.

The dominant feature of the interior is the broad altar bay with its mosaic vault of the Virgin and Child flanked by the archangels Michael on the left and Gabriel on the right. This mosaic dates from the 1130s and is the oldest remaining wall art in the cathedral. More than 2.5 million stones of over 1,500 different colors were used to execute it.

The style is largely Byzantine, with certain Georgian characteristics in the linear depiction. It was probably done by local artists who studied in Constantinople. Other works covering the walls date from the 13th to 18th centuries and reflect the fortunes of the church and the royal and ecclesiastical directives as to when and in what manner sections were to be restored or repainted.

In the eastern pan of the south chapel arc frescoes that date from 1291-1293 and depict King David VI Narin in both royal attire and monk’s robes. This chapel served as his mausoleum and contains fresco fragments from the 14th century.

In the narthex (west portico) are wall paintings from the first half of the 12th century. They depict the third and fourth Ecumenical Councils, which met in the fifth century, and are interesting for the stylistic insights they provide and as documentation of church history and politics. The councils were critical in a dispute among various church factions in the Caucasus at the time depicted.

In the north chapel of the main church arc frescoes from the 17th century combining the life of Christ with Georgian historical personages. The lower register of the south wall has portraits of King Giorgi of Imereti with his family. The upper register portrays the Annunciation, the Birth of Jesus, the Entry into Jerusalem, and the Crucifixion. On the north wall are, among other scenes, the Raising of Lazarus and the Last Judgment.

Perhaps of greatest interest is the portrait of King David the Builder on the eastern portion of the north wall in the main church. David, crowned, is depicted as founder, holding the church in his hands. This is one of the most beloved images in Georgia. It is the only surviving portrait of this great Georgian king. To the left of David is the Catholicos of western Georgia, Evdemon Chkhelidze.

Continuing from right to left are: King Bagrat III of Imereti, Queen Helene, their son King Giorgi II. Prince Bagrat, and Queen Rusudan. Slightly above is the depiction of Emperor Constantine and his mother Helena. The cross in their midst iconographically establishes his preeminence as the archetypal Christian ruler. These frescoes are from the 16th century.

Christ Pantocrator fills the dome of the cupola, and the four Evangelists occupy the four spandrels beneath. In the drum, standing between the windows, are 16 prophets and kings of the Old Testament. The murals in the dome date from the 17th century and arc signed by an artist named Tevdore.

The core cubic structure supporting the octagonal belfry may well date from the 12th century; the belfry itself was added in the late 13th century.

The church of St. George

Located to the east of the main church, this mid 13th-century church is a simplified miniature of its larger neighbor in conception and design. Of architectural interest here arc the two short pilasters with capitals in the west that support the cupola, hi marked contrast to the larger quadrangular ones found in the cathedral, these, in conjunction with the low arcades, suggest initially the characteristics of a basilica rather than the domed cruciform structure we expect at this period. Their presence here, and consequently the overall design of the interior, is very unusual and bespeaks a retrograde transitional style.

This church was burned by the Turks in 1510 along with the main church. All frescoes date from the 16th and 17th centuries. New Testament scenes are combined with scenes from the life of St. George and historical figures, tavadi or princes, of western Georgia. These have recently been restored and arc beautifully eh.ve, with a subtle Oriental delicacy. Of great interest is the Persian style of dress worn by the princes. This reflects the political realities of the time in which Sassanid Iran dominated and certain obeisance had to be paid. A portrait from the 16th century of King Bagrat III is on the south wall.

The church of St. Nicholas

West of the main church, between it and the roofless ruin of the Academy building, this two-story 13th-century structure is an architecturally peculiar element within the monastery complex. The lower level of arcades seems to function almost as a gate from the Academy to the main church and may have been a symbolic but necessary transition point at which students could change their focus from worldly to spiritual concerns. The upper-level cruciform structure is reached by an outside stone staircase on the northside.

The hall of the Academy

West of the Church of St. Nicholas, this building, along with the cathedral, is the oldest structure in the complex, begun in 1106. Within, the low stone benches along the sides are still visible, as are the niches for books and the stone pedestal for the master. The portico at the entrance was added later, in the 13th to 14th centuries. Some scholars believe that the positioning of the Academy with a long north-south axis was a means of emphasizing its secular function and thereby distinguishing it from the holy status of the church with its elongated east-west longitudinal axis.

King David’s gate

The entire monastery complex was surrounded by a high stone wall. David the Builder himself asked, as a sign of humility, to be buried in the entranceway of the southern gatehouse so that those who entered would walk over his tomb. The stone slab has an inscription in Georgian: “This is my place for all eternity. I own only this now.” The structure over King Davids grave dates from the 12th century.

The gate of the entrance was made in 1063 in the city of Ganja, in present-day Azerbaijan. Demetre I brought it as a trophy from a war fought there in 1129. Only one half of the gate remains and an inscription in Arabic states the circumstances of its arrival in Gelati. The lost half had an identical inscription in Georgian.